I find myself inspired by Steve Wheeler’s What is Learning?, a concise gem of a blog post, that argued in its final paragraph:

I find myself inspired by Steve Wheeler’s What is Learning?, a concise gem of a blog post, that argued in its final paragraph:

The exponential rise in user generated content on social media sites bears testament to this, and when these kind of activities spill over into the formal learning domain, previously well established learning theories are challenged. We now see the emergence of a number of new theories that attempt to explain learning in the 21st Century. These include heutagogy, paragogy, connectivism and rhizomatic learning. One of the characteristics of learning through digital media is the ability to crowd source content, ideas and artefacts, and to promote and participate in global discussions.

This reference to 21st century learning theories, as well as his helpful incorporation of hyperlinks, sent me clicking through to Rhizome as a mode of knowledge and model for society.

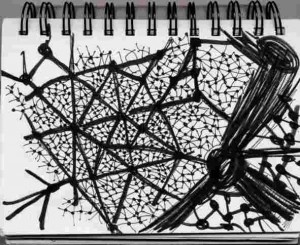

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari use the term “rhizome” and “rhizomatic” to describe theory and research that allows for multiple, non-hierarchical entry and exit points in data representation and interpretation. In A Thousand Plateaus, they oppose it to an arborescent conception of knowledge, which works with dualist categories and binary choices. A rhizome works with planar and trans-species connections, while an arborescent model works with vertical and linear connections. Their use of the “orchid and the wasp” is taken from the biological concept of mutualism, in which two different species interact together to form a multiplicity (i.e. a unity that is multiple in itself). Horizontal gene transfer would also be a good illustration.

As a model for culture, the rhizome resists the organizational structure of the root-tree system which charts causality along chronological lines and looks for the original source of “things” and looks towards the pinnacle or conclusion of those “things.” A rhizome, on the other hand, is characterized by “ceaselessly established connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.” The rhizome presents history and culture as a map or wide array of attractions and influences with no specific origin or genesis, for a “rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo.” The planar movement of the rhizome resists chronology and organization, instead favoring a nomadic system of growth and propagation. In this model, culture spreads like the surface of a body of water, spreading towards available spaces or trickling downwards towards new spaces through fissures and gaps, eroding what is in its way. The surface can be interrupted and moved, but these disturbances leave no trace, as the water is charged with pressure and potential to always seek its equilibrium, and thereby establish smooth space.

I love the notions of multiplicity and intermezzo. I take issue with the postulate that disturbances leave no trace and there is no beginning; I think that everyone and everything makes an impact, and cause-and-effect is real. I don’t mean to reduce complexity to linearity, but to suggest an absence of precedents and antecedents seems impossible.

In terms of vernacular, I think “rhizomatic learning” is a tough sell — and a tough spell, for that matter. Who’s a fan of the silent H? I’ll tell you who: Nobody. Participatory learning might be an easier moniker to describe this same concept. (Does it describe this same concept? How does PLAY!‘s definition of participatory learning compare/contrast with this one? Stay tuned!) Maybe I’m letting my geek spots show (and maybe blogging at all let that cat out of the bag, to mix metaphors), but I appreciate rhizomatic learning’s adoption of a model from the natural world. This reference might help to settle anxieties, perhaps, by reframing our 21st century context as organic and established rather than artificial and novel.

I think that what so many people find unsettling is the notion that we’re somewhere we’ve never been, and we can’t anticipate what will happen next in the near or distant future. Stephen Jay Gould, an evolutionary biologist, posited that history is better described by punctuated equilibrium rather than modest, constant change. That means, mutation and rapid change occurs, then nothing. Pause pause pause. A flurry of activity! Pause pause pause. Perhaps we’re in one of those periods of punctuation… and therefore equilibrium is around the corner. It’s possible.

Or perhaps, to refer back to Steve Wheeler’s initial musings, we’ve shifted from one natural way of learning — constructivism, which might be modeled by a cell’s growth/operation/division — to another natural way of learning — participatory learning, which might be modeled by a rhizome’s nature. Wheeler concluded:

That’s why I want to ask the questions: What is learning? Does it differ from learning prior to the advent of global communications technology? Does learning now require new explanatory frameworks? Your comments on this blog are welcomed and discussion encouraged.

I’m about to drop him a line. I welcome you to do the same.