This past week of Art Detectives encouraged participants to examine an artifact and consider, “How was this made? Where was this made? When was this made? Why was it made? What does it tell you about the people and culture who produced it?”

This past week of Art Detectives encouraged participants to examine an artifact and consider, “How was this made? Where was this made? When was this made? Why was it made? What does it tell you about the people and culture who produced it?”

As we spent the past few days presenting the children’s process and products at Open House, scavenging tourist-hungry avenues for souvenirs, rejiggering next week’s curriculum, and visiting ancient temples, the significance of these questions loomed large…

How does a well-to-do Indian parent discern the magnitude and value of a child’s learning from a: (hieroglyphically) carved bar of soap, (rose petal and) watercolored picture, (papyrus-inspired) weaving of paper bag strips, (ancient Greek-inspired) painted clay pot, (Roman mosaic-inspired) arrangement of construction paper pieces? Our EMP Art Gallery offered parents a chance to explore the means of production, experimenting with the materials that made each piece. And the sheer quantity of *stuff* was convincing for this audience.

So how does a well-to-do Indian parent discern the magnitude and value of a child’s learning from: a child-invented toy pieced together from recycle materials? What if this artifact looks unpolished? What if this is the only tangible product of the week? How does this parent see the process, and how worthwhile is the process if the product fails to impress? Our teaching team hatched schemes to unveil process and multiply products, but it was somewhat of a struggle. Were we hired to: a) deliver process to privileged children; b) deliver process and teach their well-to-do Indian parents about the value of process; or c) deliver process, teach about process, and still deliver product? C, I think, is the correct answer. And is that bad? Are progressive Americans too prone to err on the other side, saying that incorrect information and/or poor quality output is okay if someone was “trying their best” or “expressing themself”? Where do we draw the line?

Haggling over products — dime-a-dozen knickknacks clogging Colaba Causeway, I thought about process. How were these scarves and nesting dolls and wall hangings and sandals and bindis and bangles and everything made, in terms of quality and labor conditions? Why were they made? To what extent do they express anything genuine about the culture, save its need to satisfy tourists? On my travels, I’ve often wondered whether the products hawkers vend embody caricaturized versions of their own culture, manufactured to reify foreigners’ (mis)conceptions of their temporary hosts… After all, how many French people wear berets? And yet, how many embroidered berets are sold at gift shops facing the Louvre? How many Senegalese people own carved giraffes? How many Indians carry elephant-mirrored handbags? And yet, back in the States, what joy will these representations of the fantastical Other bring?

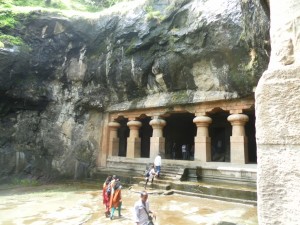

Exploring product — the cavernous temples on Elephanta Island, rock-cut shrines to Shiva dating back to the 5th-8th century, I wondered about the who in the process. Who were the people involved in the construction of this work — the visionaries, the models, the carvers, the apprentices, the clergy, the worshippers? I’ve had the privilege of touching ancient stone all over the world, from Jerusalem to Tours, Athens to Bergen. I used to wonder about the hustle and bustle of long-gone marketplaces, wished I could touch the remnant and be hurtled magically back through time. On Sunday, though, despite my recent engagements with commerce, I didn’t think about marketplaces. I thought about women. What role(s), if any, were women given back then? Were they allowed to touch tools, carve stone, pray in the holy of holies? Did they collude in art and religion’s exaltation of the phallus? Outside the temple, two nursing mothers — monkey and dog — tended to their clingy young. Was that the lot of ancient women as well, kept from the high-profile artistic and spiritual by the down-to-earth artistic and spiritual — child-rearing?

This week of EMP is dedicated to toys — creating new products from recycled products (e.g., used waterbottles and containers, bottle caps and bits of fabric and packing foam, etc). So much stuff. Our objective is to focus on the process, the development of ideas, blueprints, and prototypes, the iterative processes of building, testing, and modifying constructions and blueprints… And yet, our questions were about the product children love best — “What is your favorite toy?”, and our process includes selling the product — writing promotional copy, designing a graphic, even shooting a commercial for the ambitious elders. Consumerism. Of course, creating one’s own advertisement raises consciousness to the constructed nature of advertisements in general, their objectives and methods, and so a case can be made for its immunizing, media literate influence upon consumerism… It’s complicated, especially since we’re beholden to pleasing our cultural community by delivering a certain quantity of product that boasts a certain quality.

Still I mull which god to worship, the god of process or the god of product… and I wonder to what extent they’re both false idols. Or vessels…

I’ve decided that I want the theme for this upcoming year to be Joy. So maybe we shouldn’t fixate on the how or the what, the process or the product, but how they make us feel. Isn’t that largely what motivates creation and acquisition — a deep-seated craving for satisfaction? So whatever floats your boat, perhaps…

To hedonism?