“Writing is, of course, Ev’s legacy. He used the process of putting felt tipped pen to paper as a means of threshing out the chaff, of refining his ideas, and, most bluntly, of thinking. Ev Rogers is an exemplar of E. M. Forster’s saying about human learning: “How do I know what I think till I see what I say?” Ev understood better than most of us that we do not know and then commit to write; rather, writing like talking is thinking, process not outcome. Creativity, as Max Weber said and as we know, is about bringing intellect to bear on the persistent and emotional pursuit of an idea until you’ve got it right. That’s how Ev Rogers engaged himself on a daily basis.”

-Jim Dearing via Arvind Singhal

I talk to myself. A lot.

There, I said it. The jig is up! But evidently, this “quirk” of mine isn’t quite as far beyond the pale as I’d originally believed. Perhaps it isn’t even abnormal at all. (The fact that I audio-record my musings… well… now we might be getting into unique territory. But anyway.) The how of it, though, is worth closer examination. So is the why.

According to the Mayo Clinic, “Self-talk is the endless stream of unspoken thoughts that run through your head every day. These automatic thoughts can be positive or negative.” The ramifications of their valence are serious. These stories we tell ourselves — about the world, notably about ourselves — structure our reality. Whether the world is a kind or mean place, whether effort can lead to change, whether we are good enough — those are difficult phenomena to measure objectively*, especially if they’re subconsciously articulated; mostly, we take these things on faith. And they not only impinge upon our psychic comfort, but they can sink or support our health. Some benefits that positive thinking may provide include:

Increased life span

Lower rates of depression

Lower levels of distress

Greater resistance to the common cold

Better psychological and physical well-being

Reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease

Better coping skills during hardships and times of stress

So how do we talk to ourselves? Gently? Harshly? Fairly? Rationally? In which modes — deliberately or subconsciously; textually (e.g., via journaling), orally (e.g., via narrating), expressively (e.g., via dancing or painting), or behaviorally (e.g., via self-caring or self-harming)?

For what purpose? Ev Rogers, mentor of my mentor, harnessed auto-dialogue to make sense of inchoate ideas and discover, in a sense, his own mind. Stuart Smalley, now Senator Franken’s (in)famous SNL character, tapped it to get through his day. In the emotion regulation game Dojo‘s current iteration, players are supposed to call upon positive self-talk in order to tolerate: a torrent of invasive questions, an unpredictable cyber handslap, and the temptation to slap back. I wonder whether this forum provides an ideal space for practicing positive self-talk. I wonder whether scenarios in which players must find the bright side in an ambiguous situation, or counter a derogation with an affirmation, might be more apt…

What happens when we steal the mic, capture the conversation, program our cerebral talkradio DJs to only (or mostly) give voice to our nascent, deep, unique truths… and rhapsodize about our beauty? How will our worlds change? Then how will we change the world?

*Is there such a thing as objectivity?

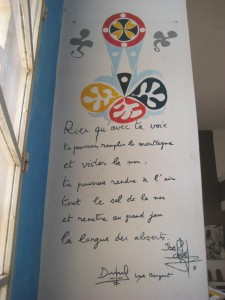

NOTE: This photo was taken in a museum in St. Louis, Senegal, Summer 2010. It reads (according to my imperfect translation skills): “With nothing but your voice/ You can fill the mountain/ and empty the sea,/ you can deliver to the sky/ all the the salt of the sea/ and bring back one great day/ the words of those absent.”