Transcript from Interview with Ruth Feldman Marcus

Transcript from Interview with Barbara Marcus Felt

Notes from talk with Raymond Marcus

Transcript from Interview with Ruth Feldman Marcus

Wednesday, October 7, 1998

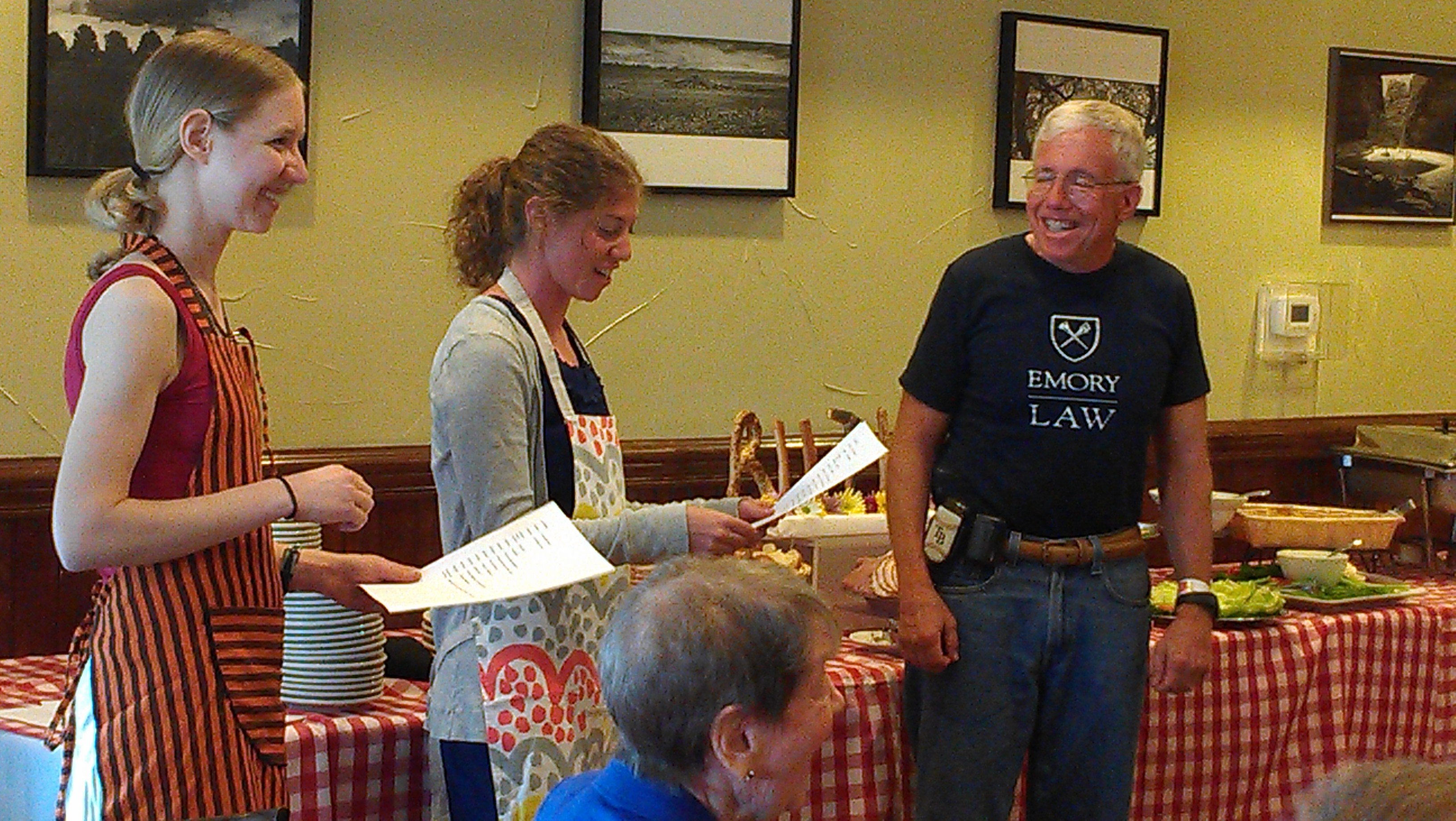

[On Wednesday, October 7, 1998, at 10:30 am, I met my grandmother Ruth Feldman Marcus at Clarke’s, a restaurant in Evanston. We “brunched” and proceeded to talk for about two hours about her life to satisfy an assignment for my anthropology class. However, I asked very few interview-oriented questions; rather, I just enjoyed sitting back and learning about my grandmother’s fascinating life. In order to preserve the integrity of Grandma’s speech patterns, I have made a concerted effort to transcribe every word that she uttered during our time together. I really didn’t know how to punctuate, i.e., comma versus hyphen versus period, so I just tried my best to fill in whatever notation felt most appropriate.

Conversation occurred before I turned on the tape recorder. Grandma told me of her initial return to college around the time Mom started at NU. At first, Grandma approached Kendall College, a junior college in Evanston. The administration wasn’t very encouraging (she was considering getting a teaching degree) because by the time Grandma would have gotten certified, she’d only have had a couple of years left to work until retirement. The student body at Kendall was also young, fresh out of high school, typically. So, she went to Roosevelt University, where there were older students (housewives like herself) and Grandma enrolled in Piano and Art Appreciation. She didn’t want to take extremely challenging courses because she was unsure about herself academically and still had responsibilities at home, taking care of the house and Grandpa and Uncle Dick and Grandma Sarah. Grandma Ruth eventually stopped her college, though, as she explains:]

RM: Then Daddy was feeling pressures from the office…

LF: From his office? I thought he owned the company.

RM: Yeah, but you know, he’s working so damn hard and Barbara going to school and-

LF: And Dickie on his way…

RM: And Dick was, and so… and it wasn’t Women’s Lib yet- I mean, I’ve never said this to anybody. So he wasn’t, he wasn’t that keen about me going back to college in the middle of all of this.

LF: Daddy isn’t too keen about Mommy going back to work and it is Women’s Lib.

RM: Yeah, well, so what I did, so, and the women wanted me to continue, I made some nice friends, they were younger than me… and uh, I took the music final-

LF: Mhmm.

RM: And I, you know, they must have felt such pity for, considering the old lady, you know. [laughs]

LF: No! It wasn’t that.

RM: It was, it was starting again because it was the whole, I was learning it the right way, you know.

LF: Mmm, I see.

RM: And then, while I was waiting, like to go in, I met one of the kids from this Shankweiler, Barbara would remember her, she was, she was the girl from Barb’s class and she had gone into music, and so she was sitting out in the lobby, you know, in the little waiting room in the music school with all of her friends and here I am. She was just a fantastic music student. So anyway, they had me play these three, I think three professors were sitting, my hands were shaking like [she demonstrates and laughs]. So anyhow, I passed, I think I got an A in the piano.

LF: Ooh, good for you. That’s not easy to do.

RM: It was basic, Laurel, you know.

LF: Yeah, but you had to go back.

RM: I wasn’t a natural, I realize that I- but anyhow, so that was the end of my college and that was when I decided to go back to work. I felt like I had to get out of the house already.

LF: Right. Is that when you went to work for Sears again?

RM: Yeah, and so then, it had been, what, 25 years or something since I’d worked.

LF: And you were a secretary.

RM: And I was a secretary, so-

LF: That was a great job back then.

RM: Yeah, but I hadn’t worked, and in those years yet, you were still doing shorthand and you were still typing on the typewriter. [laughs]

LF: Right. They might still do shorthand today.

RM: Yeah, but the shorthand I had learned when I was in high school… Pittman…

LF: Your high school’s name was Pittman?

RM: The, uh, the method of shorthand was Pittman. And there were like three methods of shorthand. There was this Munson, which I guess was. Pittman was the hardest one to learn but the easiest to read back. So, I had been a good student at that, I… So, uh, I wanted to take a refresher course and I called the high school and uh, the only they were using at that time was this Gregg which was a much easier shorthand to read, uh, to learn but harder to read. Pittman had three levels and light and dark strokes, so it would practically… spell itself out-

LF: Interesting.

RM: -whereas this Gregg was all forms, and so, you could learn it easier because you didn’t have to memorize something, but I think it was more difficult to read back, to transcribe. Well, there was no… there was no Pittman class, you know, I called the Adult Education I guess… Anyhows, I get a call and they had dug up this little old lady who must have been at that time, she was in her seventies now that I think back, but at this time she was this little old Jewish lady from Rogers Park, I think… and I don’t know how many people we had in our class, they recruited her and we practically… we’d walk her to the el or to the bus. We, we watched her like a hawk to make sure [laughs] that she’d make it, you know.

LF: That’s so funny.

RM: And, uh, I forget how many of us were in the class.

LF: Was it adults exclusively?

RM: It was adults at Niles, uh, uh, did they have a North at the time? No, it wasn’t North, we had to be going to Niles East. And we nourished her and so while I was still in the middle of the class, we started in September, I think, I went to Sears cause that was how I’d gotten my first job, you know, so… ago. They had a Midwestern territory office. On Skokie Highway and Lincoln Avenue which wasn’t far from the house and I thought, “Well, I’ll try it.” I talked my way into, the same thing that your mom goes up against: I hadn’t worked in 25 years! And there was this office manager, a Miss Ryan, she was an Irish lady, unmarried, and uh, must have gotten a bang out of me. So we had lunch at the cafeteria there and she said, okay, then I had only wanted part-time work because I was, you know, Dickie was in his third year, Barb was… and then my mom would come home over the summer, you know… so part-time work, you feel a little less responsible.

LF: You could make dinner.

RM: And that was again, that was before they realized that the housewives would come back, are good employees and they do as much work part-time as their full employees do full-time because they give you a full day and they’re grateful for working and they’re not kids.

LF: They’re efficient.

RM: And they remember the work ethic.

LF: So Miss Ryan said, “Okay, Mrs. Marcus”?

RM: Oh, and I forgot, before that, where I tried Sears, oh this is how it worked, where I tried Sears, I went to a temporary agency and they sent me to Sears-

LF: Oh really?

RM: – to do, to do something. It might have been around Christmas, before Thanksgiving, they had some kind of typing work.

LF: That’s ironic.

RM: So, it was must have been something quite basic and it was real good for me because it got me to using the typewriter again.

LF: Was it electric by then?

RM: It had to be… Wait! No, it wasn’t electric. No, it wasn’t electric, cause I didn’t get to use the electric typewriter till, uh… I’m trying to think when the electric came out… It had to be- no.

LF: I was just curious.

RM: Yeah, no, it wasn’t electric yet, Laurel. It wasn’t electric yet. The electric came out while I was working.

LF: I remember you telling me about the transition, between pounding and lightly tapping.

RM: Well, you know… So then that gave me the idea to go to Sears because I got a couple, I got a couple of jobs working for Sears, temporary, cause the lady said, “You like to go to Sears?” -the temporary lady; it was a day here, or two days, you know, something. And that’s when I went to Miss Ryan and, uh, so she started me, she too, she gave me, she assigned me some job working in this department and I get there and I’m going home and it turns out they want me to file it was in the Law Department. And I had all of these briefs and so she was going to be you’d be filing till you were blue in the face, all day, and uh… well, anyhow, I did that for a week and I was real upset and I went back to work and I said, “I thought you said,” (I went back to Miss Ryan) “I thought you said you were going to let me, uh, uh, do secretarial work,” I says, “All I’m doing is filing.” I think I was getting maybe two and a quarter an hour-

LF: Well that’s good.

RM: Oh yeah, so you know where I’m coming from. That’s why today, everything today, you know, you know-

LF: It must be so ridiculous.

RM: It’s so crazy, you know, and the expression among all us oldsters are, you know, we were “Depression-oriented.” So then she says, “Well, they were supposed to, uh, you know, let you do both things.” I says, “I can do a lot more than filing.” So, she, uh, about a week later, she sent me to the department where Miss Merrill was.. and then again I was only, I was, there was a nice girl there and she was secretary to two people, to Esther Merrill and to another man and so, I was to be her assistant. You see, Laurel, you gotta work your way up.

LF: Right.

RM: So…

LF: That’s cool that a woman had a secretary back then. What year was that? That was about 1968, 69?

RM: Yeah, yeah, she could have bought and sold all these men. She wrote beautif- she, oh, she had such drive, she was such a dear, she took a liking to me. Anyway, it wound up that, uh, I think Rosalie who was the girl there, I can’t remember whether she wanted to work for someone else in the department or something and Esther said that she wanted me to work for her and the other fella. And that’s how it worked out. I don’t know, maybe by then I was getting two-fifty an hour (laughs). And she was real nice so my time was real flexible: whenever she wanted me to come, I don’t know, I was working 20 hours a week… oh, and that first summer, Grandma was coming home and I told Miss Ryan that I had to take time off, er, no, Grandma needed surgery that’s when she had, uh, she’d had a rash that was on her rash that was neglected; anyhow it turned into something, we all had a heart attack, cancer, we thought, and so, uh, you know, so it was a whole long story, but anyhow, we went to the surgeon and of course they said that it would have to be removed.

LF: A mastectomy?

RM: A mastectomy and I said, you know, Grandma had bigger breasts than I do and I said, I said, “You know, it’s only a skin thing, maybe you don’t have to take the whole breast off.” He was a cruel guy and uh, he took, he removed the whole breast and uh, and you know, she never needed follow-up treatment or anything, I’m sure had he not done that, I mean, done what they do… This was like, barbaric in those days, you know, they figured, “Oh, she was a lady,” I think she had to be in her late seventies, early eighties at the time, they figured, “what does she need it,” you know. I’m thinking, you know, it’s hard to believe the strides we made. So anyhow, I had told Miss Ryan, you know, my mom needs surgery… anyhow, I took the summer off and I thought that would be the end of my job. In the fall, I got a call from Miss Ryan and she says, “Well, when are you coming back?”

LF: That’s wonderful.

RM: Well, but you know, it’s the feeling when you think back and it isn’t that long ago, but you know, women are still asserting themselves. And it’s like today, when I was coming down, it must have been Carol Moseley-Braun on WBEZ and they were, people were calling in and they were asking all kinds of questions and again they go on this abortion thing.

LF: Oh gosh.

RM: And how does she feel about it and so forth and how far does she think, uh, when is an abortion okay and so forth and then she said that the Supreme Court mandated it and so forth, and uh, she said, you know, regardless of what she believes, she said, you know, she believes that, you know, in her mind, you know, she would never do an abortion but-

Waitress: Everything all right?

RM: Oh, everything’s great. Thanks. -But she said, it’s not for anyone- besides, she doesn’t think it’s right for a bunch of people in Congress to dictate what a woman can do and what a woman can’t do, she said. And uh, she quoted something, I can’t recall, but a woman has her own rights, they can’t tell you, uh… I mean, what you can do and what you can’t do, they’re violating your civil rights. And so it’s still going on, the women are still fighting.

LF: I know. [laughs] They definitely are. I’m taking a class on social inequality and it’s just mind-boggling-

RM: Yeah!

LF: -to see who has the real power in this country. It mostly deals more with lower class and upper class- RM: Yeah.

LF: -more than men and women-

RM: Oh yes.

LF: -but women are part of the minority structure that have been, you know, denied jobs.

RM: Yes. So, it’s just amazing, you know, they can’t give it up, I don’t know what bothers them, what bothers them? Is it any of their business? And then she says she thinks it’s terrible they wanna make, that a woman who’s been raped, she says, should have to bear that child. She says, it’s cruel!

LF: What kind of child is it going to be, you know?

RM: Yeah… You know, you don’t know… It’s a crime. Well, that’s the story. Well… It’s been such a revolution for women, just since your mom’s time. The reason it’s so vivid in my mind is ‘cause she was a part of it, she was in the middle of it, you know, otherwise the years wouldn’t stand out so clearly as to when it happened and so forth, but it was while your mommy was probably in her junior year that it all- the Vietnam War brought it all about… But, she created so many problems too, you know, Betty [Friedan] did that, that you could have it all. But it’s a big sacrifice.

LF: How so?

RM: For a woman, I mean, you get married, you have children, you have your career- you get pulled from all sides. And if you don’t stay with it, say you start your career when you get out of school and then say you get married and you work, I don’t know how many years, and then you want a family. And then you, you want to stay home, I mean, is it so terrible? And so, I don’t know, whether maybe you stay home a while and then you go back and you’ve lost time, you’ve lost your seniority, and then they give you a hard time at some places, you know, “Are you going to have any more children?” “What if the kids get sick?” I mean, you know, you’re not the same person you were when you don’t have children and the women get bought. And what are you supposed to do?

LF: That’s true.

RM: And you know, your mom was conflicted and she stayed home and then when she went back, it was as if she’d never worked, never had experience-

LF: Really, it was that bad?

RM: Sure, and she had to start-

LF: She had a lot of experience.

RM: Yeah, but they wouldn’t recognize it because it was 20 years later or how many years later.

LF: Yeah, but people are still the same.

RM: I know, but, uh, but your mom was working with kids and given the same amount of money as kids that had just got out of college… and the reason she did get back when she did is that she said if she loses any more time, she’ll never get a job. So, you know, had she worked all these years, you know, she could’ve been anything by now. You see? So then there was a real interesting article by this, Barbara Brottner of the Womenews on Sunday, you know, that section?

LF: Sure, I like that section.

RM: And she wrote that- I don’t know how old she is, how old her kids are, but she wrote that she’s back after four months, she took a leave of absence and-

LF: For four months to have a baby?

RM: No, I don’t think she had a baby, she just took a leave of absence to like, to like, refresh herself and she said how much easier it was and she had time for the kids, I don’t know, maybe she had a couple of kids, I don’t know how old they were, the house was more orderly, the children were… evidently she has small children, the kids were calmer, she wasn’t harried, and she enjoyed it and she enjoyed going to the grocery and not being in a hurry, you know, and the long and the short of it is here she is, back again. She said, you know, Why am I back again? And she said of course she loves her work and so forth, and I think she likes the money, she said it gives them the vacation and so forth, and then she says the bottom line is that if she waits for the children to get a little older where they can be on their own, she’ll send in her resume and at a certain age, they’ll throw it in the garbage. So, she’s implying that you’ve got to stay with it or else you’re out.

LF: How long did you stay with it after you went back and you were working for Sears?

RM: Oh, so I stayed, I worked for about… we had this real nice relationship so my time was real flexible. I think I worked for about nine years and then Esther Merrill who I worked for; again, she could have bought and sold everyone in the department, the men- she wrote so beautifully. And the head of the department, whenever he wanted to make a speech or something, he would call Esther and ask her to write it and she was so capable. But she was a woman too, see, and she was so vital and she was so full of life. She had to be, I’m trying to figure out how much older Esther is. I don’t know, maybe six, seven years, and uh… uh… anyhow, there was a rule and she was fighting it: you had to retire at 62. And they were pushing her out. She didn’t want to leave in the worst way and they could have, you know, they could have made it until 65 or something, but anyhow, she had to retire and uh, so then when she left I was still in the office, I was going to work for a couple of different people and the store in Northbrook (they were building Northbrook Court) the store in Northbrook, they had a Sears and they needed, they needed everybody and we were interviewing- oh, and before that, the supervisor, you know, the manager of… who had originally hired had gone on to other things and we had a different manager and for the last year or so before I left she had been after me to work full-time. But I was still afraid and then they started interviewing for Northbrook Court and she says, “I want you to go down and interview.”

LF: You must have been real good.

RM: Then, so, I interviewed… Anyhow, I got the job to be secretary to the manager of the Northbrook store. And uh, that meant full-time. But by then, Dickie was in law school already and Mom was married and uh, I thought I’d take the plunge. And uh, oh, it was such an exp- the store wasn’t quite ready when I went in and it was so exciting. It was altogether different from working in a corporate office, it was a fantastic experience, very different. They really… and I worked for the manager and the assistant manager and of course, it was a disaster from Day One because the store never took off.

LF: Yeah.

RM: The whole Northbrook Court didn’t take off.

LF: Really?

RM: Oh, it was… The people in the area didn’t want Northbrook Court. They didn’t want anything so commercial and they fought Sears maybe, I don’t know, maybe 10 years or something, and Sears persevered- they wanted that Northbrook Court. And so then they made all kinds of rules, one side I think was Highland Park and one side was Northbrook and they made rules you couldn’t cross the str- make turns to go over to the northern side of it, I think that might have been Highland Park, and it was over who’s going to get the money, the taxes, the whole bit, and they persevered. And they rammed Northbrook Court and they promised that they’d put up all of this shrubbery and make it so that it wasn’t a commercial enterprise in the middle of that residential area. And they made such changes, they changed the roads, and Waukegan… Lake Cook and Waukegan didn’t go beyond Waukegan and Sears, they extended Lake Cook to go west and they changed the entrance to go into Edens. I mean, the whole landscape changed.

LF: Yeah.

RM: But it was, it was a disaster. And uh, and then after a year, my mom wasn’t well, and uh, I… I went to Florida and came home and decided I’d stay with, I’d stay with Grandma. And the store was so , uh… it was, you know… Anyhow, so I left, and of course, you know, Sears went out, Montgomery Ward went out, and I think until maybe they put the theaters in, it still has never really taken off.

LF: We used to go there a lot, but maybe that’s because it was close.

RM: Well yeah, but the people there all literally boycotted Sears because these were,uh, wealthier class and you go in to buy a gift from Sears and they didn’t wrap it fancy, I mean, they, they weren’t geared for a North Shore crowd.

LF: I getcha.

RM: And the only thing that they would buy at Sears, they wouldn’t buy the clothes, that was kinda beneath them, was their appliances and stuff. And they were so demanding, the people, I remember because so many of the complaints would come to the manager, and uh, they denigrated Sears, you know. And that one lady who put white carpeting in her house called and she said that when the men come, unless they take off the shoes coming in and out, they couldn’t come into her house.

LF: Let’s hear it for the North Shore.

RM: Also, there was a Magnin’s at that time, that was a great store, and they left and there were a couple other, you know… Anyhow, it’s like piece of history.

LF: That’s exciting.

RM: That’s why they put the shows in.

LF: Yeah, well, I thought that the shows was to compete with Old Orchard. They were supposed to put ‘em in years ago.

RM: Yeah, but, they did that to, to uh… until they got that through and they had to promise the people all kinds of things and if you look at, if you look at Northbrook Court, on the south end where there’s homes in the back, they had to promise them all the shrubberies and all the things-

LF: The retention pond?

RM: Yeah, so… Anyhow.

LF: How did Grandpa feel about you going back to work? He wasn’t that positive about the education; did he at least feel different because you were bringing money in?

RM: I felt different. I had a feeling of, uh, of uh, of independence. It’s a very difficult thing, Laurel, because I had worked before I got married-

LF: Right.

RM: And uh, I gave some money to my mom and some for me but I was, I was independent, you know. And then… I didn’t realize, you know, when you get married, maybe I should, you know, we didn’t have that much of an income; actually, I had been making more money. See, I didn’t always work for Sears. I worked three years for Sears and then, and then, when the war came along, middle of the war or something, I was recommended to work for this fixture and lamp manufacturers and I was the secretary for the general manager; and that was a Jewish firm and it made such a difference. And I was working at Sears (my first job) when I was a kid, you know. There was anti-Semitism there, overt.

LF: You told me about it.

RM: Yeah.

LF: They’d ask if you had any holidays to take off…

RF: Yeah. So anyway, I worked for Turner Manufacturing Company for three years and two of them, of course, Daddy and I- Grandpa and I were married but he was overseas. And what I should have done probably, and during the war there was a freeze on salaries; but, I started out, when I left Sears, they were going to give me $25 a week which is a lot of money.

LF: Okay.

RM: And I went to Turner and uh, I think they were going to give me the 25 and after a week or two, I was kind of sorry I had gone and the hours were different and I was so used to Sears and I said I don’t know if I like it so well, so they gave me a raise [laughs].

LF: Woohoo! There you go, Gram!

RM: But I wasn’t thinking of that, and the long and short of it was, I had a real nice job- I should have stayed! But Grandpa was coming home and we had never… see, and in those days, the women didn’t work. So they, I was going to get them, and then they were going to give me a bonus at the end of the year, and they were going to give me, and then after the war, because there had been a freeze on salaries, in 45, you know, after the war ended, the freeze went off, and they offered me, they said they’ll start you off at 45 or 50 dollars and I had said no, Grandpa’s coming home- listen to this! I think of all these things and I was looking all over to get an apartment before Grandpa came home. You couldn’t get apartments because everything had stopped during the Depression, and nobody had built anything, and then all of a sudden, all of these fellas are coming home and families are starting and you couldn’t get an apartment for love or money. And that’s a long story, so then I got this apartment all the way on Kenmore, because my girlfriend’s uncle owned the building, I think I told you, and so it was so far from the West Side, and the place I worked for was on the West Side. The long and short of it, I says, no, I’m going- when my husband comes home, I’m leaving. I told them three months in advance, I was being honorable, they thought I had rocks in my head… And then when Grandpa came home, the, you know, it was a family business, they were starting, and he was starting at $25 a week! [laughs] So, and of course, our rent at that time was $42.50 a month, and gas and electric, you know… so, you know, your scale of money was altogether- But still, so you, know, my mom had been very frugal, we lived a nice life, but very- we always lived within our budget. So we allotted so much a week for food and, and I didn’t take any money for myself, you know, that was the thing, that’s what I’m trying to tell you.

LF: Did you talk to Grandma?

RM: No no, no, I’m talking about after I was married with Grandpa when he came home. No, with Grandmother it was no problem- I gave her half and I kept half.

LF: But your half went into yours and Grandpa’s account, as opposed to a private account?

RM: No, no, Grandpa’s- the way I saved money when Grandpa was gone, in the army, was he’d send home a check, the army sent overseas pay or something or no,or they sent the wife, if you had a wife, she’d get $50 a month, so we got a check for $50 a month, and I’d put $25 to it and bought a $100 bond every month that Grandpa was gone. So we had, I don’t know, I don’t know how much money we had when he came home, cause we had never had a wedding and such- that’s another story. But, but anyhow, so when Grandpa came home and we were figuring out our money, we were being real frugal, you know, so I didn’t take any money for my own personal needs. And what I needed for my own personal needs, you know, sometimes you want to go to lunch, you want to, you know, you don’t want to have to ask your husband for everything. See? So, it’s a big change. And you got, you know, not that maybe he would have said no, or what if I had wanted to spend another five- but you just don’t do these things, you know, you’re young and you’ve got idealistic… And, uh, of course he got a car- it wasn’t as if we were poor, but we were living within his salary. And then, like, at the end of the year he would get a bonus, but still, you , you didn’t figure that, you know, so that’s what I’m trying to say. So then when I went back to work- there I was! I mean, you’re independent again and I says to Grandpa, I says, “This is my money [laughs].” I didn’t give that to Grandpa. And so I say, you know, I wouldn’t use it for any household things, you know, it was just for me, you know, and I put most of it away in my own account, I have my own account. So that’s why when went back to work, your uh, you know, it’s a horse of another color!

LF: Yeah.

RM: You’re independent.

LF: Yeah.

RM: Can you follow it?

LF: Yeah sure, that’s how I felt this summer with Dad.

RM: Yeah!

LF: I would never ask him for money-

RM: Yeah.

LF: -and it made me feel good.

RM: Yeah.

LF: That, you know, if wanted to splurge, I could.

RM: Yeah!

LF: That’s the same way it is now, I put so much in my savings, Dad hasn’t had to give me an allowance or anything like that. I take care of it myself and I balance my own checkbook.

RM: It’s an altogether different feeling. So that’s what, you know, so, you know if you’re in a certain category, sad to say, some women have to work in order to pay the rent and the whole thing, but if you’re at a little different level and you’re both equal, you know, you feel differently about having your own income. So, anyhow, it was kind of an evolution I think in women’s rights and women’s equality… Anyhow, now, Laurel, if you ever need, if you ever need money, don’t ever hesitate, cause I worry, because I know how you are-

LF: Thank you.

RM: -and I know the feeling, and you know, you can’t do everything, you can’t go to school and make money, you know.

LF: A lot of people do.

RM: Well, you’re a freshman, I mean, it’s such a big adjustment… So.

LF: I appreciate it, Grandma. I’ll let you know if I need anything.

RM: I’m serious. You know, something, something will come up and you can’t use up all of your savings, you’ve got four years.

LF: I’ll see, hopefully I’m going to try to get something part-time, maybe next quarter. You know, because, I am still adjusting right now.

RM: Of course! I mean, you can’t, I mean, it isn’t fair, we didn’t send you to college to support yourself.

LF: It’s so expensive…

RM: Well don’t worry, we’re taking care of that.

LF: Yeah.

RM: So don’t worry about the tuition, it’d be expensive wherever you went.

LF: How did you guys take care of Mom’s and Uncle Dick’s tuitions?

RM: It was no problem back then. We lived modestly and I was just uh, I was just uh, I always felt, I wanted everything for the kids, you know, and you know, we weren’t uh, Grandpa always made a nice living and we lived modestly, and that was what we always saved our money for. And Mom, uh, when she had to go to school, I was worried, this was uh, before the girls had gotten so independent and so forth and some of my friends’ girls had gone away to school and gotten homesick. I was real worried. And so, first, I wanted Barb- your mom and I were thinking about a girls’ school.

LF: Yeah, I remember, Chatham.

RM: And there were a couple other, there was Lake Erie, and there was another school, and I wanted- I didn’t want- so I was real worried. And then, uh, and I had told your mom, you know, whatever school she wanted, she could go to, no problem. Tuition wasn’t as bad then, I think, I think, I think, even figuring, uh, the difference in money values from then and now, I still think the money proportion is much greater now on a college. So, uh, when your mommy got accepted here at Northwestern, well, originally she was going to live home because she couldn’t get housing, so it would have been the same if I had send here, if she had gone down to Illinois. Then the housing opened up and uh, there was never, uh, there was never any problem. And with your mom too, I think, now if I think back, maybe you know, we didn’t understand, but she too didn’t want to ask for money and stuff. She was working part-time… you know, I think, I think, you gotta kinda reach the kids, you know, now when you think back, and make her feel more comfortable about accepting your money because you guys get this chance just once, you don’t want to be burdened by other things if we can help it, put it that way. So, I didn’t, I didn’t realize at the time maybe I could have made her feel, you know, more comfortable about her taking things. I can’t remember now how we worked it. Your mom was working, I can’t remember the first year, she taught Sunday school and then, over Christmas she, uh, she worked as a waitress over in Glencoe. –She’s probably told you these stories.

LF: I knew about Sunday school, I didn’t know about the waitress.

RM: She went in Hubbard Woods and uh, I don’t know, by the time she had to pay for the uniform or something, you had to wear a little apron, a little apron and a cap, I don’t remember-

LF: Oh gosh.

RM: -and there was like a coffee shop, like a hang-out, something like this [Clarke’s], and she’d take the car and I don’t know if they gave her a dollar and a half an hour, I don’t know what, and tips. So she came home one time, she almost fainted.

[the tape ran out here; in the interim, Grandma explained about Mom’s babysitting jobs during college]

RM: And Dickie when he went to school, Dick too could have gone to any school that he wanted. And he went down to Illinois. But Dick had worked… all through, uh, I think maybe from the time he was 16 or something, I don’t know, or 17, when he didn’t want to go to camp anymore. I don’t know how old Dickie was, I think he started going down to Marcus Brush, and he worked over Christmas. And uh, I can’t remember when Dickie worked. And so, he had his money, he said and when he went down to Champaign, he said he didn’t need any money from me. I gotta ask him how that worked, I can’t believe he could have had all of that money, so that he, uh… you know, so we paid his tuition and everything. I mean, we never pressed the kids but I guess, like you, they felt, uh, they felt funny. But really you shouldn’t because we want you to go to school and you’re in the school to learn and it’s only such a short time. You shouldn’t have to be worried by school.

LF: Oh, okay.

RM: But I mean now, you tell me, you just remember that. I mean, so that’s how it works. So those people, you know they had that offer, they haven’t come through, huh?

LF: Well, yeah, I emailed ‘em and I called them, and they just don’t have work right now, but when they do, they said they’d send it.

RM: Yeah, well, they can’t, they can’t, I mean, it was too good to be true.

LF: I know.

RM: All right.

LF: When it happens, it’ll probably get busy around Midterms or something like that.

RM: Yeah, maybe, maybe, I don’t know, what was their business, maybe business isn’t so great either, you know, these are crazy times now…

LF: And they sold the company, and-

RM: Oh!

LF: -I’m not sure what’s going on.

RM: That’s probably what it is, it’s transition.

LF: And you get projects, you know, it just really depends on when the clients come.

RM: Yeah, right.

LF: So…

RM: Yeah, there’s no point, you know, they say it would have been nice, but, uh, there’s no point in doing anything about it now, I mean, it’s just too much to give up your school, and I would feel terrible.

LF: It’ll all be okay.

RM: Don’t worry about it.

LF: I’m not worried, I’m really, I’m not. [laughs] I just spent $40 on groceries yesterday, I’m fine.

RM: Yeah, that should hold you for over a year, right?

LF: Yeah.

RM: No, I mean it’s crazy, your money doesn’t go too far.

LF: No, it really doesn’t.

RM: And uh…

LF: You hand over the credit card and you’re shaking, you’re like, “Oh my God…”

RM: Yeah.

LF: But-

RM: I mean, but this is the way it is.

LF: I know.

RM: So I mean, you know, supposedly they’re going to pay you umpteen sums, it seems like a lot of money, and then when you go out in the world today, it’s nothing.

LF: I know. Oh well. Water under the bridge… Tell me something about, like, your early life – When were you born, where were you born?

RM: When was I born? It’s like the Dark Ages now when I think back. Uh, it was an innocent time, you know, I was born, uh, you know my brother was eight years older than I was.

LF: Right.

RM: My mother’s had, oh, times were rough and uh, my mother had a real difficult time when my brother, you know, in her uh, in her pregnancy and delivery.

LF: Oh really.

RM: And uh, so, uh, I don’t know, maybe she had decided maybe she was only going to have the one.

LF: Was there birth control back then?

RM: And evidently whatever, you know, we never discussed anything, but whatever it was, she was very careful. And then my, my aunt, was her sister, you know I keep talking about my cousin Marcelle who was a month older than I am.

LF: Right.

RM: Now she was, you know, my Aunt Helen might have been 10 years younger than my mother, my mother was the oldest one.

LF: Right.

RM: So, my Aunt Helen had, she had a son, Ernest, who was about three, I guess. She told my mother , Maury was going to be eight, you know, that she was pregnant. And this is the story my mom tells me, and so when she heard- and they were close, you know, because my Aunt Helen was the first girl, after my mother there were three boys, three brothers, so my aunt was the first girl- so, uh, my mother said, “Oh my God, Helen has a girl and I don’t,” and so she got pregnant and my aunt had Marcie April 25

LF: Oh yeah?

RM: And I was born May 25 and I guess she had a difficult time, like a three-day labor, I don’t know, you hear these stories. Maybe today they’d do it differently, she tells me that the doctor [?], she could hear it in her subconscious, they said, “Thank God she she’s got a girl.”

LF: [laughs] That’d be the only thing that justifies-

RM: Yeah, so… You don’t remember my mom cause you were a baby when she died. But she was a very independent lady, a very loving person. So I had a real nice childhood, it was like being an only child, Maury was eight years older, and uh… They were Depression years, I mean, but we didn’t know we weren’t, uh… that times were hard because everybody in the area, we were all- everybody was in the same boat. And we didn’t know that we were living in a Jewish ghetto because your world is small. We all lived in apartment buildings.

LF: Where?

RM: On the West Side of Chicago, so like, Roosevelt Road- I think you might have heard of that street. And uh… my folks were very ambitious, my father was a barber, I mean, he was barber and I don’t know if he was, you know, not by- uh, I don’ t know how come he decided on that, but when he came from Europe, uh, it might have been the easiest thing to learn or something. But he was really, he was a wonderful mathematician and uh, in those- they didn’t have education, they were learned in Hebrew and the Jewish faith of everyday, you know. So it wasn’t as if they were illiterates, see that’s the difference with Jewish immigrants, even though they didn’t get educations, they were… they, they were learned in the Hebrew- [waitress enters] Yeah? Oh, take this.

LF: [laughs] Thank you.

RM: So, uh, and they were ambitious and they- well, it’s a whole long story.

LF: That’s okay.

RM: Do you have to go back to school?

LF: No, I’m fine.

RM: So I should look at the car outside, I gave it an hour and a half.

LF: Well, do you want to go sit in the park or something?

RM: No, no, because I was going to see if it needed money.

LF: Oh.

RM: So anyhow, when I was born they had built this… the area was brand-new at that time, it’s hard to believe the West Side- it was west, it was west of, of, of the area where all of the buildings were, it was all big empty lots and so forth and they had built this- well, they had had it built, it was a 13-apartment building and at that time, uh, the rules about how you finance it and everything were very lax, and so you could put down a small amount of money and then pay the mortgage off and then what happened? So I was born in this building-

LF: Oh yeah, were you delivered by a midwife?

RM: No, no. Well, I shouldn’t say I was born in this building, when I was baby we came to this building. My mother was in the hospital, with my brother she went in as a, uh, as a… as a clinic case. You know, so she didn’t have to pay. And with me already, she was a regular patient. So, and at that time, she stayed two weeks, you stayed in the hospital two weeks after you were born. Of course, it was even worse cause they didn’t let you get off the bed. Things were all together- they didn’t realize that you should move around a lot so really, by the time she came home, she was weaker than when she went in!

LF: Yeah.

RM: Yeah. But anyhow, so I was born in that area, and there were three apartment builidngs and there was a park, a big park, it was like a playground. And it was a very happy childhood. But what happened, the Depression came and they lost the building and uh, we lived there rent-free – it’s a whole long story. But, so everybody was in the same boat, and – [looking out the window and noticing people milling around a car] Is that my car?

LF: No, it’s an Acura.

RM: Oh, I must be the next one.

LF: Yeah, you are, you’re the next one.

RM: So, it was a very happy childhood cause the park was across the way, they flooded it in winter and we ice-skated on it, they had a swimming pool and all kinds of equipment and I lived directly across the street. And the kids, the parents were all so busy, you know, taking care of their own lives and, and you had, let’s say you had 13 apartments, that was this one building, and across the street was this big apartment building. So you start to think about how many kids-

LF: It must have been at least fifty, you know?

RM: There was a million kids all the time, and nobody went to each other’s houses because the kids didn’t have their own rooms as such, and kids didn’t have toys, you know? So you were always outside! And there was always somebody to play with. And you were never at a loss, you go out, there was this kid, this kid, this kid, or there was the park.

LF: Right.

RM: So it was, you know, really a carefree time, although times were very difficult- nobody had money and some, I didn’t realize now, some of the kids were on char- But, for the most part, Jewish people would rather die than take charity. But none of us knew that we were… that they were poor, as such. So… and school for me was a lot of fun because my brother was eight years older and so I had nobody to play with in the house. My father, in those days, they stayed open- his place of business was a long distance away, so he’d leave the house like seven o’clock in the morning, he wouldn’t be home until eight o’clock or so at night.

LF: Wow.

RM: So he never had dinner with us, he always had dinner separately, my mother would keep the food warm. And so, the house was very, uh, very lonesome.

LF: Yeah. What kind of hours did Grandma work?

RM: Well, Grandma at that time was home until I was about thirteen.

LF: Oh.

RM: Actually, what could she do? She had no education.

LF: What about the deli?

RM: Well, so wait. So then when I was, I was going to be in eighth grade, and there was a small little restaurant, a small little restaurant not far from where my father worked. At that time it was called the South Water Street Market, it was the produce market. All of the trucks came in with the farm goods and you had buyers, uh, people who had stores, you know, fruit stores and grocery stores and would come and buy the fresh produce everyday. My father’s barber shop was in that area and this little restaurant- I’m trying to think of how big it was. It might have been this square, I guess… [indicating area]

LF: Really.

RM: And then you had to walk down two stairs and it had a counter, and some tables, a little kitchen. It became available and you know, my mother had, you know, they had been wanting to do something. My mom was a real good, she was a real good cook, she was a real good everything, she was fast, she was… And so, for $600 you could buy that store.

LF: Where did you have the money?

RM: And she got it from my grandfather. She got it from my grandfather, borrowed the money and bought this little restaurant. And I was going into eighth grade, Maury was, she wanted him to go to school, he went to this school of accounting downtown, and uh, she would get up about, five o’clock in the morning and the man who lived upstairs, the family who lived upstairs, the man had a, he was in a kind of produce business in that South Water Street Market, and he drove, he had a truck that could, and he would be going down every morning and she would wait for him and he would take her. And I think, so this little restaurant, the reason she took it it was supposedly short hours, and uh…. She’d open it I think around six o’clock in the morning and then it would close around three o’clock I think, and she cleaned up and then she had to take the streetcar to come home.

LF: Right.

RM: So I don’t know, she’d come home around maybe five o’clcok.

LF: And then would she have to make dinner?

RM: And she usually brought, she usually, she’d be coming home with shopping bags from what she had cooked. And she went in and she… the cook didn’t come or something, anyway, she let the cook go. She was very- she was an amazing person, lot of determination, so she did the cooking and she did the shopping and my Aunt Ethel, who was out of a job at the time, came and she was the waitress and… And I would be home alone, you know from the morning until she came home. And my father didn’t come home until-

LF: Eight.

RM: Til eight, nine o’clock. But you didn’t think anything of it. I’d come home for lunch and go back because school, you know, you stayed in school- in the same school, you know, you started and you didn’t have junior high and stuff, so the school was about three, three blocks away and I did everything that I would have done had she been there: came home, I made lunch, and uh… I came home after school, practiced the piano, you can imagine how… And then, and wait for her to come. Clean up the house, or else go outside in the winter and go shopping- Let me run out, Laurel. There’s a police car.

LF: Sure. [Tape stops during Grandma’s sprint outside to feed the meter.]

RM: Yeah, so that was, so she lasted, uh… She had the store until she got so sick because she worked so hard. She was getting up six o’clock in the morning, coming home at five o’clock, and doing everything- you know, I did what I could and on Saturday what I thought was cleaning the house and stuff, I would do that and then go down to the store cause she was there on Saturday til about two o’clock. And there were no washing machines in those days and she was very frugal, every penny she saved and she would wash, now I don’t, she would wash clothes in the bathtub in the house and she would do that on Saturday or Sunday and hang up the clothes on the radiator, I can’t- you know, it’s just, life was so different then and she did everything and she just wore herself down and uh, I think in April of that year, cause she had gotten it around January, the store, in April of that year, something like that-

LF: Do you remember what year it was?

RM: Well, I, I had to be, uh… I was 13 in May so if I was born in ’22, so that was say, ‘35. The heart of the Depression. They usually give you different shots in school, you know, for all your- And I don’t know what shot this one was, uh, I think it was a series of three shots or something and you would line up and the doctor would go through all of these kids, and I got an infection, a terrible infection in my arm.

LF: From the shots?

RM: From the shots. And you never went to a doctor. You had to be dying to go to a doctor. So, uh… Evidently the whole arm had to swell. And uh, and then I had a fever, my mother had to go to work and I’m laying down. Anyway, the damn thing opened up finally by itself. I remember my mom took me to the drugstore, [laughs] across the street. I mean, this is primitive!

LF: Yeah.

RM: And uh… And uh, I don’t know, he said just keep it covered or something, so we put a handkerchief around it, the damn thing is draining, I got an arm like this. So there was one thing that happened to me. And then I got, and this all this time, while she was having the store, then I got, over spring vacation, I got a sore throat and I was sick and my mom had had to leave me every morning and go, and I had this high fever and I’m lying by myself in bed.

LF: What about your aunts?

RM: And my Aunt Helen, she’d come, I remember she’d come over to have a look at me, bring some soup or something and go back. And after, after a week, or more, and I wasn’t getting better, finally called- God knows how my mom had to feel- finally called, uh, a specialist in. And in those days, the doctor would come to the house. So, this ENT, he was just starting out, this doctor, and evidently, he was going to be an ENT guy, he came and in my mom’s bedroom- cause she had had a doctor before that and he didn’t see anything, he said it was just a sore throat and he was the one, that’s what happened, he was the one that recommended this ENT guy because he says he doesn’t see anything. So this ENT guy came to the house, that’s when, and at that time the doctor, she gave him $5 for his visit, and that was a lot of money. I don’t know what she gave this ENT guy, and it was an abscess under my tonsil, and he did it right in the house-

LF: He did what, a surgery?

RM: Yeah, he told my mom to hold my arms –

LF: Huh!

RM: -and he, he burst the uh, the little abscess.

LF: Oh God!

RM: In the house! The blood and the… I mean this is, these are things, I mean, they sound so primitive, right?

LF: Wow!

RM: I mean, he brought some lamps over to see.

LF: [laughing]

RM: So my mom had to go through all of this. I don’t know what she paid him! Of course I got better after that! [laughs] It’d be worse with the abscess.

LF: You’re lucky, yeah.

RM: Cause he said it was ripe already and I’d been sick for two weeks. So, that had to be over spring break, so I mean, those two things. So my mom was on the ver- got real sick, I mean, and so thank God they were able to sell the restaurant, in May or something, so they had it about five or six months.

LF: I didn’t realize.

RM: And they had, I don’t know how much money, she paid my grandfather off, she gave him interest- this is how you did things. And she had, I don’t know how much, cause she saved all that money, it was, you know, money that she herself worked so hard for and she was like, sick, sick all win- sick all summer, I mean, she was like on the verge of a collapse. She was so determined that she just wore herself out. And so, I remember, you know, where she’s lying in bed and I’m trying to do what I could and I, I remember I was washing stuff, I remember washing, we gave stuff to the laundry and all the dark stuff, the socks and stuff I remember washing ‘em.. And she really, you know, had tried to protect me, I didn’t do, but I was trying to do what she used to do. I remember rubbing the dark socks, you know, [laughs] in the sink or in the bathtub.

LF: Yeah.

RM: Well, and, uh, thank goodness she recovered. And then it took about, another year, in the meantime she still wanted to make money. It took another year, I was in high school. I was going to go into my second year of high school and my father- and they had been researching delicatessans and stuff. My father would go- let’s say, my father would go and evidently there, you go to a broker, I don’t know how he found out, and, and he would go and look at these different stores that would be for sale, different businesses. And he would sit all day and the count the customers that we coming in the store, trying to figure out-

LF: The turnover?

RM: Yeah, how much money would be, how much it made, how much would be left. And in my second year of high school he came on this delicatessan.

LF: Wow.

RM: And so he still worked, you see, it was my mom’s, and then it’s another whole long story, my brother had gotten married and couldn’t get a job and so he and my mom opened that delicatessan up and I would come to, when she first got it we were still living on 14th and Kildare. On Saturday I would go home, I would be home, I would clean up the house in my fashion and then walk to the store which had to be, I don’t know, two, three miles and then the second year we moved from there, we moved to, got an apartment that was like half a block away. And I would go every day after school. So that was our home- never used the house. She worked, and I would take a dollar a week. Cause you know, money was so hard, you know, she worked, I wouldn’t take money-

LF: Sure.

RM: You know? And she would tell me, you know, just, just take whatever you need. And I couldn’t take whatever I needed because how could you take? But I would stay, I would work, and do whatever, and that lasted until, I was working a year already, I graduated school, and then I was going to go to college. There was this junior college not too far. And I started in February and uh, I had wanted to go to Champaign, you know-

LF: What did you want to study?

RM: I was probably going to, what could a girl, I was going to go into teaching or library, library science. And, uh, but I figured, oh, I suppose I was dreaming, I don’t know what, I said well, I would go in September, I would start at Herzel. And uh, I went to Herzel which was, I don’t know, two, three miles from the house and I loved it. And uh, I took short-hand again, I took English, I forget what I took, and uh, it was a lot harder than high school because when I went to high school, I mean, it was in a fancy neighborhood and stuff, but the education wasn’t that great. And I’d never had English in high school, grammar even. [laughs]

LF: Wow.

RM: I can’t even begin to tell you. Anyhow, I enjoyed it and I got a job. They had a program for kids funded by the government, uh… to help kids going to college. So I applied because one of the girls I was going with said she was applying. So I applied and I got this grant, and I don’t know what it was going to be, I don’t know, $15 a month, [laughs] I don’t know. And I got a job working for the short-hand teacher part-time or something.

LF: Right.

RM: And then, I don’t know, I was in school, I only got one mark maybe two months, I started in February, the end of March. My mom was going to the store and we had a, a late snow storm and it melted and there was ice and she fell on the sidewalk and she broke her wrist. So, I stopped school-

LF: She couldn’t cook with a broken wrist?

RM: She couldn’t, no. And I, uh… Not that I could cook but at least I’d be in the store. And uh, so I quit school, I was working in the store and uh, and uh, I think I was going at night. I went to night school, I don’t know, I was always shy- you wouldn’t think that, would you? I went to Austin and I was talking public speaking. [laughs] Can you believe it? Well, don’t ask, that was a whole other story. And working in the store, I think I went once a week to Austin. And I don’t know how I came on- but you know, education wasn’t that stressed. And uh, and then my Aunt Molly- do you remember Aunt Molly?

LF: I think so.

RM: Yeah. She, you know, she had been divorced and she, she was working at Sears on the West Side on [Artington?]. And I knew short-hand, you know. And so then, when my mom was getting better, I was really thinking I’d go back to school, so this was in May or June. There was an opening in her department, for a secretary. She gave ‘em my, and she says she’s got a niece, and so I went and, and that’s…

LF: That’s…

RM: And then we had the store for maybe another year, and then the war came along. And so, first the war came along, and then they were going to make the, I don’t know if you ever heard of it, the uh, is it called the Eisenhower Expressway?

LF: Yeah.

RM: At that time it was called the Congress Street Expressway. It was just going into, they were just going to start doing it and where our store was was going to be torn down to make way for this expressway.

LF: You get compensated for that, don’t you?

RM: Pardon? Well, I don’t think they gave my mom what she would have made if she tried to sell it. But anyhow, they left the store and I was working, so that’s how come I would give her half my salary. $16 I got a week, I didn’t realize she was saving it for me. And uh… and then she went out and got a job at Sear’s, she couldn’t read.

LF: Your grandma?

RM: My grandma, after my mom-

LF: I mean, yeah.

RM: That’s what I’m saying, she was an amazing lady.

LF: Your mom.

RM: During the war, you know, there was a shortage of help. She went in, it was this big warehouse and offices on the West Side that right now, they, they donated all of that land, Sears, for reclamation on the West Side.

LF: Right.

RM: And it was a huge thing, it was almost four or five blocks it went. So they had their mail order, she went down there, and uh, she worked in the mail order and they hadda, they hadda schedule orders. And so it went by numbers, you put, you had all these pieces of paper I think by numbers and you had to file ‘em in different cubbyholes, so she could do that.

LF: Yeah, sure. She couldn’t read Eng- what was her English-speaking ability, wasn’t it kind of-?

RM: She did half and half, but she, you know, she understood English perfectly-

LF: Right.

RM: And she spoke, but I don’t know, you know, it wasn’t as if she didn’t speak English.

LF: Right, I just remember funny stories-

RM: Yeah!

LF: -about her not understanding on the telephone-

RM: Right.

LF: -things like that. “Barbara no home,” hunh [indicates slamming down receiver].

RM: Yeah, well [laughs], she spoke better than that. But she spoke, I mean, she’s- you know she would speak half, you wouldn’t know, you would begin in English and end up in Yiddish.

LF: Right.

RM: But no, she was able to, you know, get along in the, in the… American world, put it that way.

LF: She just worked and worked-

RM: Worked and worked, and she was on her feet eight hours a day, you know- this was what we would call “unskilled labor,” no?

LF: Yeah.

RM: And she continued working at that til after the war.

LF: Meanwhile your father was still a barber?

RM: And my father was [laughs]- and he made just a certain amount of money, very little. And they saved their money, and uh… I don’t know how many years later, they bought, they bought another- my father was always, the idea of real estate. They bought another building with my Uncle Irving, they didn’t have, my father almost fainted when my mother said- cause that was his hobby, he would go to real estate, there was like a real estate company not far from where we lived and he would go there every Sunday cause that was his hobby, he would go over all the things that were being offered-

LF: Huh.

RM: And sometimes he would sell for them and get a commission. And there was this one building and there was my Uncle Irving who was interested and they decided to buy this apartment building, I don’t know how many apartments- 26 or something…

LF: Wow.

RM: I forget the amount of money, they didn’t quite have it, my father almost fainted when my mother said that she had umpteen and umpteen thousands of dollars. He couldn’t believe it. Of all the money she made working, she saved. All those years.

LF: In a bank?

RM: In a bank.

LF: Was she earning the interest?

RM: Well, they were paying very little in those years.

LF: I know, but after the Depression, weren’t people scared of banks?

RM: Well, after the Depression, and where all the banks closed, she lost money, my grandfather lost money, she lost money-

LF: And that’s why you had to sell your building.

RM: That’s why the building went into foreclosure is what it was, yeah. Uh… then new laws were enacted to, to protect you, see, there’s all kinds of new laws went in after that, like insurance laws and so, so the money was in the bank and he never knew about it. Or I don’t know, was it in a safety deposit box, I don’t know, cause I used to go with her all the time because I would do the writing, you see.

LF: Ah.

RM: And so they were able to buy this and they were, I don’t know, $10,000 shorter, but then Grandpa and I, Grandpa and I were married and we saved our money and we gave them, we borrowed, Grandma- the money that they were short, I forget how much it was, and Grandma paid it back within a year. So, so that’s, and they figured that from that building they would have an income, so that after the war, they let her go and Grandpa came home and so I wasn’t home with my salary, she took in a boarder.

LF: Really?

RM: [laughs]

LF: She just kept on going.

RM: Can you believe that? Talk about resourceful.

LF: I know.

RM: She never stopped. And so, my uncle, my Aunt Helen’s husband, you know, they were always fairly wealthy, he couldn’t understand, couldn’t understand how she did it, and in her later years, you see, she was independent. Cause she-

LF: She went down to Florida?

RM: Yeah, and it was all her own money because she bought the building, she had her income from the building, and then of course Social Security but if she was getting, if she was getting $50 a month, it was a lot. And, and we were very fortunate that she was well. She had Medicare, but we never had, we never had any supplemental insurance, but she never really needed it. Medicare had just come in- but that’s, that’s the way she [lived it?] -and she left a nice estate. From, from pennies.

LF: I know. What was it like, wasn’t just her father and she who came over from Russia?

RM: And my uncle, my older unc- her, her brother who was next in age who was a year younger, the three of them came.

LF: Where were they living in Russia, I know it was on a farm.

RM: Well, they were living in the, it has to be in the Ukraine area in some, you know, some real small village and I don’t know what city was it- you know, now that you begin, you know, at that time I used to think it was far-flung in the country, but God knows… In those days, you know, the only way you could go was like with a cart and horse, so who knows, if, you know, if the city was-

LF: A couple of miles?

RM: -it would be a, it would be a long way. But they lived out there and my, my grandfather was like, like an overseer in a wealthy man’s, they would call it the [poor end?], the man was like the big boss or the big owner, a gentile, and he had all this land-

LF: Were they like share-croppers or something?

RM: And my grandfather marked the trees that had to be cut down. He never did- my grandfather was such a gentleman, and he- Dick reminds me of him, that little build, like Dick, he had a little goatee, and ah… He was never learned and he never did heavy labor [laughs]. And my grandma… And so they had this little farmhouse, this little house, and maybe, I don’t know, two, you begin to think about it, was it maybe two rooms or something with a big, with a big fireplace, you cooked over the fireplace evidently.

LF: Wow.

RM: You begin to think, this was going back. My mother was born in… she came to this country in about 1905 or 1906. We never knew her exact age or when she was born because they didn’t keep records. It had to be in the… she had to be born, I think I once made up 1892.

LF: You think she was born then?

RM: Yeah, 1890, 1892.

LF: She was about 14 when-

RM: She was 16.

LF: She was 16. Oh, okay.

RM: And we never did get, you know, the exact year, I think it was about 1906 when they came to the United States.

LF: Well so, 1892 to 1906 is only 14 years.

RM: So then 1890.

LF: Yeah.

RM: 1890.

LF: Wow.

RM: And so you would say “When were you born?” She knew that she was a spring baby, but she didn’t, they didn’t have birth certificates or anything. So you know, that’s your back- you know, when you grow up with such a background, it uh, it forms you.

LF: Sure, definitely.

RM: So then when you, you know, then already when I got married and Grandpa, you know, we were like people of means already and so… you know, my mom tried to do everything that she didn’t have for us, so the fact even that I had a high school education, my brother went on to get a, to become an accountant. And then already, we never had a car, and then already when I, when I got married, whatever I had, I wanted my kids to have more.

LF: Yeah, look at us-

RM: See?

LF: -this is ridiculous.

RM: So I think to myself she would be so proud to see, you know, to see what her grandchildren, what her great-grandchildren have accomplished. You know, she was so proud of, uh, of Dickie and Barbara and uh… You know, for her, the transition, when you think of it, the transition was so tremendous-

LF: Yeah, they left Russia because of-

RM: Of, of, first there were the pogroms-

LF: The pogroms. Were they ever effected by those?

RM: Well, I think so. And uh, they were, they were in this little village, so I don’t think, I don’t think they ever had one come through, but they knew about it all around, their lives were… very precarious. And then what they were doing, they were going to recruit the boys. They figured, the Russian government, they figured that they would get the boys, and, and uh, they would convert the boys, once they got them in the army, they would get rid of the “Jewish problems.”

LF: Sometimes they would kidnap the boys.

RM: Or else they would kidnap them. So here, so my mom was 16, I think they used to take them at 16, so my Uncle Sam was-

LF: He was 15.

RM: -he was 15 and then my Uncle Morris was like 13, and my Uncle Harry… so she had three boys after my mom and they were all getting to that age. And so, they had to leave and my mother said that my grandma, she had, uh, she had loving, my grand- her grandmother, so that would that be… that would be my great-great-grandmother, it would be my grandmother’s parents. They lived in a town, they were fairly well-fixed, you know, and they were heart-broken because they were, my mother said she used to love to go there and they also lived quite a distance, I don’t remember what they did. So imagine to see their daughter and that time she had about seven- eight kids, leave, and know that you’ll never see them again. And, you know, when you think of all these things… and they had to, you know, first my mom came with her two brothers- no- yeah-

LF: With her brother and her dad, I thought.

RM: My mom, yeah, three of ‘em.

LF: How did they have the means to buy passage?

RM: Well, they, you know, they, my grandfather worked, they must have saved money-

LF: For a wage?

RM: And they, sure, I mean, oh yeah, I don’t know how he got paid, we never went into it. And my grandma’s parents, whatever they did too, you know, they weren’t, they were better than peasants, you see, they were always, they were always able to support them, there was always enough food, there was always…

LF: They were lucky.

RM: Yeah, so, uh… And the boys, the boys went to school, but of course my mom didn’t, the girls didn’t go to school. They didn’t go to the regular school, they went to the Jewish school, the yeshiva, I don’t know what it was called, where all the little Jewish boys went, and they started going when they were-

[The tape runs out now. Grandma and I continued to talk while I jotted down notes in my notebook; here are those notes, somewhat reconstructed so that they’re in proper English]

– Jews “always” knew how to read and write. [This is a generalization; what I think Grandma means is that literary was well-entrenched in the Jewish culture. We discussed the immigration situation in America later in the day and we agreed that a major difference between Jewish immigrants and those from other backgrounds is that transitioning to American culture isn’t as difficult for the Jews because they already are acquainted with reading and writing and overall erudition in society.]

– The West Side was the original Jewish ghetto- Maxwell, Roosevelt, and Halsted streets – she didn’t know it was a ghetto back then.

– Our family entered the USA through Baltimore because Jewish philanthropists (mostly German Jews) like Levi Strauss wanted opportunity to be available. These philanthropists resettled Jewish immigrants in Georgia and Texas so that not everyone would be concentrated in New York.

– The family ended up in Chicago because Grandma Ruth’s grandpa had family in Chicago.

– Immigrant families were very close-knit, providing security, comfort… Jewish people were so grateful for all they could get here and “they wanted to be American so bad, sometimes I think they threw away the baby with the bathwater- they became citizens right away… they just wanted to be part of the American culture. Even their Jewishness they tried to modernize.”

– Parents and value system were Grandma’s largest influencing factors.

– “I wasn’t that far-seeing- for all of my independence… I wanted to live so-called American dream” [this is in reference to quitting her job after the war] – it was a responsible job and very demanding and she had to be a housewife as well.

– They were different media messages during Grandma Ruth’s and Grandma Sarah’s eras- while Grandma Ruth was married, if a woman had to work, it was a slight on her husband, that he couldn’t support her; while Grandma Sarah was married, if a woman worked, she was enterprising.

– Grandma Sarah used to tell Grandma Ruth, “When I wanted you to work, you didn’t work.[after WWII] Now I don’t want you to work, you’re working.” [later in Grandma’s life, when she went back to Sears]

– Said Grandma, “I was on the cusp of two worlds.”

– Grandma Ruth’s birthday was May 25, 1922.

– She was 23 when Grandpa came back from the war.

– Grandpa Ray lived next door to Grandma Sarah’s deli, so his whole family would come in and sit, talk, and socialize- “In the gentile world, it was like a tavern. Here it was a Jewish deli.”

– During the war, Grandma was thinking of joining the government and going overseas- Grandma Sarah said no, “she thought I was nuts.”

– Grandma mused to herself, “Why didn’t I go to night school while Grandpa was in the army?”

– “We were so ambitious for our children. You got to the United States and there were so many doors that were open that were not open in Europe. So if you had the slightest bit of ambition…”

– Grandpa Ray went to Wright Junior College and he was going into accounting.

– The Marcus Brush company opened post-WWII.

– Oscar’s [Grandpa Ray’s father] cousin had a brush factory in New York, so Oscar sold the brushes and paints. Art [Grandpa Ray’s older brother] joined him in Chicago.

– So how did Grandpa Ray get into the company? “Art got an attack of appendicitis in the spring season in Detroit and looked at Raymond, gave him the car, the different stops, and said to him, ‘You’re it.’”

– Grandpa would be gone for six weeks at a time.

– The GI Bill of Rights gave soldiers college for free and $50 a month- “that’s where you got the educated class after the war.”

– Buster [Bernie, Grandpa Ray’s younger brother by six years] went to the University of Illinois

– Ray didn’t want to go to school, he felt that he was a man already- he was starting a business, he was married.

– “Grandpa could have been anything.”

– Art was 10 years older, he wasn’t going to listen to Buster, who was “just a kid,” despite Buster’s business course.

– They had incredible patriotism for America.

– “We [Jews] have come so far- so many professions are open, there are quotas in schools.”

– “Your mom could do anything, I keep trying to convince her- also Dick. If she put her mind to it, there isn’t much she couldn’t do.”

– “The thing that I’m most proud about- I’m first generation, your mom’s second generation, you kids are already third generation. For me, it’s like you came over on the Mayflower! Our family has been here 100 years already.”

– Grandma learned how to drive when she was pregnant with Uncle Dick.

– Grandma Sarah wanted to learn how to drive, but the man who was teaching her brought her out to Devon Avenue [a very busy street] her first time out and scared her off- still, that was incredible that an older woman would want to learn how to master that new piece of technology.

– They were all guided by the American Dream- “we were programmed, and we fell for it. That’s what we were put here for, that’s what we felt.”

– Grandma Sarah used to tell Grandma Ruth: “You get all your pleasure from your children.”

– Grandma kept Barbara out of school for two weeks when she had a cough.

– There were nine kids in Russia, Aunt Ethel was born in the United States, she was four years older than Maury.

– A Jewish mother is devoted (self-sacrificing), giving all to her children and she didn’t think anything of it, she wouldn’t think twice.

– “Our whole family was gentle, and the kids are the apple of your eye. My mom always put the kids first.”

[Following this conversation, Grandma and I went for a walk around downtown Evanston and strolled by Lake Michigan. We continued to talk about the Jewish cultural heritage and my life at college. I showed her the student union and my dorm room. I dearly love my grandma and it was a wonderful visit.]

Sunday, November 8, 1998

LF: So, Mom, what do you remember about how Grandma Sarah died?

BF: Well, she died February first, which took my mom and I-

LF: 1981? 1982?

BF: 1982, just before your second birthday, which took us by surprise ‘cuz we kinda felt that if she’d made it by February, she had come through the winter, and it didn’t seem fair to die just as spring when was coming. But the day before she died, she insisted that Grandma Ruth drive her to our house out in Glenview to say goodbye to me and Grandma Ruth didn’t quite get what “goodbye” meant, but said “okay,” because she was so insistent that she was coming- she had “to go to Barbara.” And she came and we all sat around the kitchen table and talked and fooled around and generally had a very nice time – no, it was during the day.

LF: So I was there, right?

BF: Yeah, and um, she was very insistent when it came time to say goodbye that she was saying goodbye, but she was also walking out the door, so we didn’t take it too seriously. I think that was the occasion also that I was in the height of my macrobioticness, and-

LF: Your what-ness?

BF: …Had stored both sugar and salt in glass containers because plastic gives off bad karma.

LF: Are you serious? Plastic gives off bad karma, you believe in that stuff?

BF: Well, bad vibes.

LF: Okay.

BF: You know, it’s, it’s less stable than glass and it can… like, [laughing]Tupperware is bad for you… So, I had, Grandma took sugar in her coffee, which nobody really did in the house but her… and I kept on putting in teaspoons of salt. [laughs] And she kept making faces at me and I just put in another one until she finally indicated we better [ ? ] and we all really had a good laugh.

LF: Now didn’t she like to keep the sugar cube between her teeth?

BF: Yeah, but I didn’t have any sugar cubes.

LF: Right, but she did that.

BF: Yeah.

LF: That’s kinda cool.

BF: And uh, so, that was the end, the last day of January, and then she left and the next day I got a call from my mom that Grandma Sarah was gone. And Grandma couldn’t say “died,” she kept saying “gone,” and I kept saying, “Then call the police,” and she kept saying, “But she’s gone,” and I said, “I understand, you need to call the police,” and then she finally said, “Barbara, she’s gone,” and I said “Oh, she’s dead, I’ll be right there.” And, what happened was, in the middle of the night, Harry must have come for her. And, because she wandered, Grandma had taken to double-locking the doors, she had a couple of deadbolts on the front door.

LF: Did she ever get out and wander in the neighborhood? Or, what do you mean by “wandered”?

BF: She had.

LF: Oh, so that’s why you really thought, “Call the police,” that makes sense.

BF: Yeah, ‘cause it had happened before, but only during the day, when the doors had been unbolted. So then my mom took to double-bolting the door… and she had walked out of the house, undoing all of the locks, without her glasses on, but she never went anywhere without her glasses because you know, us glasses-wearers, and without her teeth, and she never went- she never let anybody see her without her teeth. So…

LF: Didn’t she also have a cane or a walker?

BF: No. So, we think that Harry really came for her and she didn’t need her glasses or her teeth.

LF: Had she mentioned to Grandma or you before that she was going to see Harry-

BF: Yes, she had told us both that Harry was coming for her.

LF: That’s specifically what she was saying?

BF: And my mom said that she had gone that night, room to room, looking for him.

LF: And then, I thought, I recalled that she had a heart attack and died before she hit the snow?

BF: That’s what they told my mom. So, I think that’s true.

LF: So, Grandma woke up in the morning and found her mother dead on the lawn?

BF: Actually, a neighbor found her.

LF: Now, when was it, was it like 1986 or something with the whole, alleged, brain tumor episode?

BF: Sarah, yeah, ’86 cause she was… maybe she was two and a half, so it was right before your birthday that we did at the Rugen Center, because-

LF: Oh, I remember that, with the puppet show?

BF: Yeah, ‘cause I had the angiogram on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17. And we thought, for a couple of days, that it could be a brain tumor or a brain anneurism.

LF: Because of your eye?

BF: My eye was puffy, it was probably my… whatever-it-is, my little malformation.

LF: Your birth-defect.

BF: I think I probably had a sinus infection that was causing a lot of pressure. And, I had a dream that my Grandma Sarah, my Uncle Maury, and my Grandma Gussie all came and stood at the foot of the bed and said, “Don’t worry, not yet.”