A workshop for City Year Los Angeles, presented February 9, 2012

- Why play? What is it?

-new media literacies (NML) definition of play: “the capacity to experiment with one’s surroundings as a form of problem-solving” (Jenkins, Purushotma, Clinton, Weigel, & Robison, 2006, p. 4)

-“Play is a very serious matter… It is an expression of our creativity; and creativity is at the very root of our ability to learn, to cope, and to become whatever we may be” (Rogers & Sharapan, 1994, p. 13).

-Besides being tied to creativity, play is also science – it is the vehicle through which one asks questions, constructs hypotheses, runs trials, analyzes results, and comes to conclusions. Particularly today, as forward-thinkers exhort innovation and policy-makers (solely, and thus myopically) extol the virtues of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), the seriousness and practicality of this should be obvious.

-“In almost every example of what he describes as “the sacred,” play is the defining feature of our most valued cultural rites and rituals. As such, for Huizinga, play is not something we do; it is who we are” (Thomas & Seely Brown, 2011, p. 97).

- What is play good for?

A1. Tinkering (agenda-less play) → innovation

-A 10-year-old’s unbounded experimentation led to her discovery of a new molecule

00:00-01:30

A2. Tinkering → discovery

-Junior Toy Inventors in Mumbai’s Expanding Minds Program learned about balance by working with sundry materials.

A3. Tinkering → personal and social enrichment

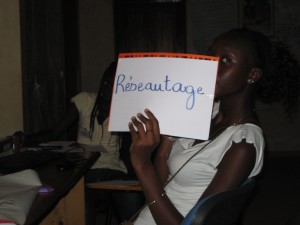

-This culturally-inspired innovation in Senegal contributed to Sunukaddu staff member/inventor Idrissa’s sense of pride and self-efficacy, as well as the benefit of learners near and far.

NOTE: This final photo is from the RFKLab, a space for innovation and community-building at the RFK Community Schools in downtown Los Angeles. Laughter for a Change uses the NMLs in its Tuesday after-school program with high school students. Improvisation is an excellent context and tool for getting at play and other key NMLs.

B1. Gaming (purposeful play) → innovation

“This is the first instance that we are aware of in which online gamers solved a longstanding scientific problem,” writes Khatib. “These results indicate the potential for integrating video games into the real-world scientific process: the ingenuity of game players is a formidable force that, if properly directed, can be used to solve a wide range of scientific problems” (Young, 2011).

B2. Gaming → discovery

“… certain games afford their players the opportunity to step virtually into the shoes of a specific profession and, through game play, become familiar with its domains of knowledge, skill base, values, identities, and ways of thinking about the world” (Joseph, 2008, p. 263).

For more about Barry’s incredible global learning and youth development program, check out Global Kids!

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Fear Factory | ||||

|

||||

06:13-07:06

B3. Gaming → personal and social enrichment

-Becoming a better critical thinker, friend, teammate, person as a result of play

Can you think of an example to illustrate this?

- Why? How does that work? Why does play produce such incredible results?

1. Flow: “the satisfying, exhilarating feeling of creative accomplishment and heightened functioning” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, p. xiii).

2. Self-efficacy: belief in one’s capacity to produce effects (Bandura, 1977)

Acting in a game demonstrates to players that they can exert power over something, that their efforts make a difference. “Fiero is what we feel after we triumph over adversity” (McGonigal, 2011, p. 33).

3. Capacity-building

Playing enriches perseverance, emotional stamina, mental toughness, and divergent thinking.

4. Community

Game-related talk (processing experience, comparing performance, exchanging feedback, pursuing mastery) builds relationships and community. “Good games… support social cooperation and civic participation at very big scales. And they help us lead more sustainable lives and become a more resilient species” (McGonigal, 2011, p. 350).

- Play and the NMLs

New media literacies (NMLs) are “a set of cultural competencies and social skills young people need” in a culture that “shifts the focus of literacy from one of individual expression to community involvement” (Jenkins et al., 2006, p. 4).

Despite their name, NMLs are neither “new” nor exclusively about “media”; rather, they are time-honored practices that support critical thinking and problem-solving.

-Why? Because NMLs are tools for problem-solving. New and old media alike pose “problems,” such as understanding new gadgets, working with dissimilar collaborators, and interpreting data. NMLs – in these examples, play, negotiation, and visualization, respectively — offer tools to solve those problems.

Other key NMLs include collective intelligence, “the ability to pool knowledge and compare notes with others towards a common goal”; and negotiation, “the ability to travel across diverse communities, discerning and respecting multiple perspectives, and grasping and following alternative norms” (p. 4)

For more information on NMLs, see newmedialiteracies.org and playnml.wikispaces.com, as well as my publications!

- Problem-solving

-Problems have an emotional piece to them — they elicit emotional/physical responses in our bodies. Certain strategies can help you to defuse or limit the emotional intensity of a problem. (You can practice these strategies via innovative video game Dojo from GameDesk!)

-Problems also have a practical piece to them — they present real barriers to maximally productive workflow. Which strategies can you invoke for managing conflict and solving problems?

- ABCDE Exercise

NOTE: My dear friend and mentor, brilliant Garden Nursery School director Jenn Guptill, co-presented this exercise with me back in 2004, when we taught workshops in supporting young children’s conflict resolution for fellow early childhood educators. A-D might be a product of the Safe and Caring Classrooms study group in which we participated, and then we added the E…

-Ask for volunteers to roleplay two characters in a contextually relevant problematic scenario

-These volunteers will play out an encounter in which they address the scenario

-Then they will see what happens when they try out steps A-E

A. Ask neutrally if there is a problem

-Do not assign blame, characterize someone as bad, or assume malicious intent; speak about how things look to you: ”I notice that when I do X, it seems like you do Y.”

-Use “I statements,” explaining how behaviors (NOT the person, just certain acts) they make you feel: “When you do X, it makes me feel like Y.”

-Invite other person to share his/her perspective: ”What do you think is happening?” “What do you think about that?” “What have you noticed?”

B. Brainstorm possible solutions to the conflict

-Both parties ideally should contribute to the brainstorming session

-Ideas should be heard and, ideally, not criticized

-The point is to establish trust and step away from putting people on the defensive

C. Choose which solution you will employ and how you will follow up to assess

-Both parties should agree to the action plan

-The assessment part is key — how will you know if things are working? When will you check in again to ensure that there’s satisfaction and open dialogue?

D. Do it!

-Get ‘er done

E. Evaluate

-This part is often left out but it allows for minor adjustments, guards against strained relations and icy silence/alienation post-confrontation, and renews awareness of/commitment to the solution (because it can be easy to fall back into old habits)

- Play for Problem-solving Activity

-Break into small groups of 5-6, work through a problematic scenario by using a mode of play

Modes of play:

1. examples from nature — think about plants, animals, etc and see if that helps you to model and problem-solve

2. roleplaying — think about the characters involved in a problem and step into their shoes, act like them and try to think like them in order to problem-solve

3. manipulatives — use assorted objects to model systems and relationships

4. art — express problem, using as few words as possible, via paper, markers, Post-Its, and other art supplies

5. narrative — turn the problem into a simple story, as if you were explaining to a young child or an alien from another planet in order to boil it down to its most essential elements and make new discoveries

6. free play — find another playful mode of exploring your group’s problem!

Possible thematic outcomes:

1. innovation: new solutions

2. discovery: new skills or knowledge

3. personal and/or social enrichment: new relationships and/or intrapersonal understandings

4. other

Possible deliverables:

1. a way to communicate the problem so that the organization (and/or multiple stakeholders) better understand it

2. multiple possible solutions, a long brainstorm session

3. one processual solution and a set of action steps and recommendations for implementation and evaluation

4. an organizational restructuring involving new working groups or work flows or communication processes, etc.

5. other

- Shareout

What did you come up with?

How did your group members work together (e.g., strategies, roles, conflicts, solutions, etc)?

-Reflections can be enriched by use of ORID (Stanfield, 2000), a protocol for facilitating group discussions that is based on four lines of inquiry: Objective (e.g., “What happened?”); Reflective (e.g., “How did it make you feel?”); Interpretive (e.g., “What is this all about?”); and Decisional (e.g., “What is our response?”).

O: What happened? Which words/phrases/moments do you most vividly remember?

R: How did it feel? Where were you surprised/delighted/frustrated?

I: What is all this about? What does all this mean for us? How will this affect our work? What are we learning from this? What is the insight?

D: What is our response? What action is called for? What are our next steps?

- Epilogue: City Year L.A. Plays to Problem-solve!

This incredible group of open-hearted, fun-loving, forward-thinking folks enthusiastically embraced the challenge to approach organizational issues from a playful perspective. They harnessed modeling clay, blocks, animal figurines, toothpicks, gumdrops, a Barrel of Monkeys, and narrative form in order to think innovatively and develop viable solutions. Thanks to Shira Weiner for dreaming up and bringing in all of these creative materials, and for inviting me to City Year in the first place! C.Y.L.A., let’s play, hook!

Listen to this recording of the group members’ fantastic solutions!

Thank you for this opportunity and please keep in touch!